November 3, 2016

Music Web International : Review

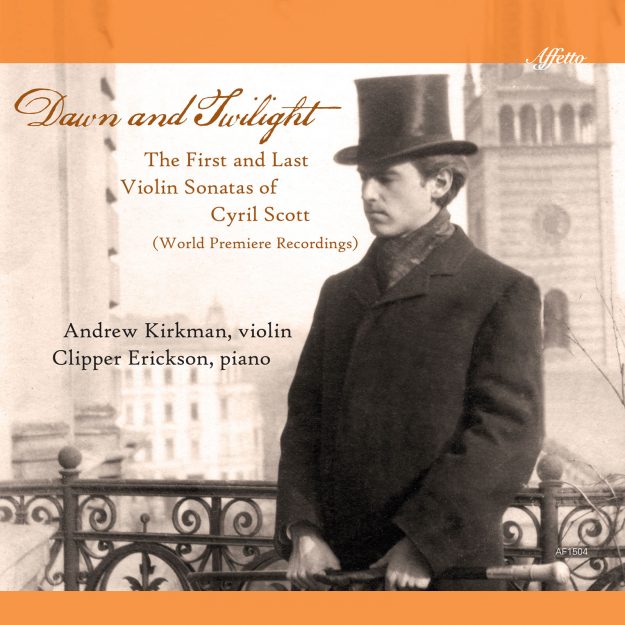

Cyril SCOTT (1879-1970)

Dawn and Twilight: The First and Last Violin Sonatas

Violin Sonata No. 1 in C Major, Op. 59 (1910) [39:50]

Violin Sonata No. 4 (1956) [16:15]

Andrew Kirkman (violin); Clipper Erickson (piano)

rec. God’s Love Lutheran Church, Pennsylvania, 11-14 Sept 2013.

AFFETTO RECORDS AF1504 [56:05]

I was all set to challenge Affetto’s claim that this disc presented first recordings. Not so quick. Andrew Kirkman, in the booklet points out that the First Sonata, as recorded on Naxos (review ~ review), is of the version Scott revised in 1956 – a year when he was much engaged by the violin and piano duo. Andrew Kirkman and Clipper Erickson, courtesy of Affetto, let us hear the original 1910 version of the First Sonata. This valuable and luxuriously enjoyable addition to the catalogue is about as third as long again as its late re-casting.

Cyril Scott was much occupied with the violin as an instrument. His own instrument, the piano, drew from him piano solos, sonatas, two piano concertos, a roaming piece for piano and orchestra and a 1900 piano concerto revived as a reconstruction on Dutton. The violin with its independence from lung-capacity and its legato capacity for spinning preternaturally long melodic lines produced from Scott a violin concerto, four sonatas and various genre pieces.

Scott’s early flowering years produced generously proportioned works and this is clear in the sumptuous dimensions of the First Sonata. The first movement – an Allegro moderato – is in a state of constant efflorescence with a good sense of forward motion. The tropical undergrowth is dense and curvaceous – a little like the Austrian Marx and Scott’s British colleague, Arnold Bax at least in his early works like the String Quintet, the unnumbered symphony and Spring Fire. The movement’s successor is a deeply affecting Andante with some really distinguished and memorable ideas. It’s rather Debussian and the piano writing recalls for me another rare British composer of that era, William Baines. The diminutive Allegro molto scherzando [4:15] is a jaunty light blend of Dvořákian ‘Dumky’ and genre salon-charmer. The expansive finale [12:47] is a lofty Allegro maestoso with that noble-ecstatic air heard in the first movement. It evinces a sustained indulgence in gorgeous soliloquy rather than oxygen-rich dynamism. It is not that there is no dramatic energy [9:25] but the predominance is one borne of a sultry hothouse. Lovers of the Delius violin sonatas and violin concerto will find much to reward them here.

The First Sonata contrasts with the Fourth, which runs to just over a quarter of an hour. It was written long after the world had, by and large, turned away from Scott as it had from his contemporary Bantock. Bantock died in 1946 while Scott lived on to the fine age of 91 but these were cruel years where the musical establishment remained obdurate against the merits of Scott’s music. While his pupil Rubbra hymned his praises on radio it would be the late 1970s before anything approaching revival would spark.

The Fourth Sonata is in three tersely concentrated movements. There is still the same flow of song in constant motion but the language is a degree cooler and can be chill at times. This is still the luxurious Scott of old (I: 3:02) but dark clouds shade the waters of Lotus Land, previously the home of Rainbow Trout, Paradise Birds and Water Wagtails. There are some gaunt pages among the trilling delights but the delights are there. These include a noble finale which breathes conviction and new life into Scott’s early grandeur.

Clipper Erickson is no newcomer to Scott having recorded for DTR a mix of Scott and Quilter piano pieces. He has always been an adventurous pianist and the latest evidence of this is a 2-CD set of the complete solo piano music of African-American R. Nathaniel Dett (1882-1943) on Navona. Dett’s magnificent oratorio The Ordering of Moses has recently been issued by Bridge. Erickson is nicely complemented by Kirkman who can search out and bear on high a lush lyricism with the very best. The apposite and straight-talking notes are by Andrew Kirkman and Desmond Scott.

The style-apt playing and warm, up-close recording are very satisfying indeed. I hope that Kirkman and Erickson will look at other rare violin sonatas including those by Coke, Isaacs and Gaze Cooper. That said there is still much to be done for Scott. Let’s hear an intégrale of the four string quartets and – more expensive yet – the major choral-orchestral work, Hymn of Unity.

Rob Barnett

The Affetto Classical Sampler, featuring nine tracks from our nine album releases, is out and it’s Free on Amazon.

The Affetto Classical Sampler, featuring nine tracks from our nine album releases, is out and it’s Free on Amazon.

Coming on October 28th a new Affetto Records release.

Coming on October 28th a new Affetto Records release. Coming on October 28th a new Affetto Records release by Elmira Darvarova and Octavio Brunetti – “Adios Nonino & other great Tangos by Piazzolla”.

Coming on October 28th a new Affetto Records release by Elmira Darvarova and Octavio Brunetti – “Adios Nonino & other great Tangos by Piazzolla”.